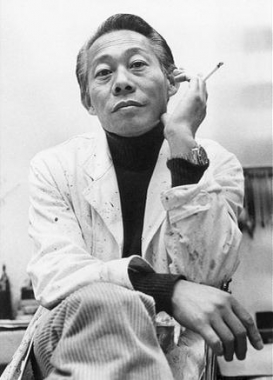

Zao Wou-Ki

Zao Wou-Ki a pioneering force in merging Eastern Asian and Western artistic traditions, was a dynamic artist who, throughout his seventy-year career, developed a distinctive artistic language that transitioned from figuration to full abstraction. He was the first ethnic Chinese artist to be inducted into the Académie des Beaux-Arts in France.

Biography of Zao Wou-Ki

T'chao Wou-Ki (who adopted the name Zao upon his arrival in Paris) was born in Beijing into a prosperous and well-educated family with lineage tracing back to the Song dynasty, which ruled between 960 and 1279. Following the Chinese tradition of bestowing names that forecast future fortune, his parents named him Wou-Ki, meaning "no limits" or "no boundaries."

Shortly after his birth, the family moved to Nantong, a town north of Shanghai, where his father, Chao Hansheng, progressed from a clerk to the general manager of the Shanghai Commercial Bank, the largest private bank in China. Wou-Ki received his primary and part of his secondary education in Western-style schools, learning English from a young age. He was an exceptional student with a particular affinity for literature, history, and art.

Encouraged by his father, an amateur painter, Wou-Ki began exploring art at the age of ten, despite his mother's less enthusiastic attitude, which peaked when he painted on one of her treasured 18th-century plates. His grandfather introduced him to drawing Chinese characters and the fundamentals of calligraphy.

During his formative years, Wou-Ki was influenced by Cézanne, Matisse, and Picasso, whose works he discovered through postcards brought back by his uncle from Paris and reproductions in American magazines like Life, Harper's Bazaar, and Vogue, which he bought in Shanghai's French Concession. He also acquired painted copies of works by Matisse, Rembrandt, Poussin, Renoir, and Modigliani.

In 1935, Wou-Ki enrolled at the Hangzhou School of Fine Arts (HSFA), where he immersed himself in the study of both traditional Chinese painting and Western techniques. However, the Sino-Japanese War of 1937-1945 drastically altered the course of his life. Despite his privileged background, Wou-Ki was not immune to the upheaval and insecurity of those tumultuous years.

As tensions with Japan escalated, China experienced a significant exodus as millions sought refuge in the country's interior. The faculty and students of the HSFA relocated to the relative safety of Chongqing in Sichuan province, where Wou-Ki spent the remainder of the war years. Following his graduation in 1941, the artist transitioned into a teaching role at the academy. During his time in Chongqing, he dedicated himself to teaching, painting, showcasing his initial exhibitions, and establishing pivotal connections that would profoundly influence his future and career.

Wou-Ki greatly benefited from the mentorship of Ling Fengmian, who pioneered the integration of modern Western techniques with traditional Chinese forms. During his time in Hangzhou, he met Xie Jinglan, a fellow student in the music department. They fell in love and married in 1941, soon after welcoming their son, Zhao. After the war, the HSFA returned to Hangzhou, but Wou-Ki had already set his sights on Paris, intending to stay there for just two years.

On February 26th, 1948, influenced by Vadime Elisseeff, the Cultural Attaché of the French Embassy in China, who had taken 20 Wou-Ki's works to Paris for an exhibition at the Cernuschi Museum's Exhibition of Contemporary Chinese Painters, Wou-Ki and Jinglan departed Shanghai for Paris. After a 36-day journey at sea, they arrived in Marseille and then traveled to Paris. It is said that Wou-Ki spent his first afternoon in Paris exploring the Louvre.

However, their two-year adventure was impacted by the changing circumstances in post-1949 China, specifically the establishment of the People's Republic of China under Mao Zedong. The regime denounced art with Western influences, leading to the removal of Wou-Ki's friend and mentor, Fengmian, from his presidential position at HSFA. The artist's father encouraged him to stay in France, despite the personal sacrifices, notably the separation from his young son, who remained in China with his parents.

Wou-Ki embraced his exposure to Western art and culture with enthusiasm. He secured a small studio next to Alberto Giacometti and took French language lessons at the Alliance Française. He also enrolled at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière to study European art. He quickly made new friends, including American artists Sam Francis, Norman Bluhm, and Joan Mitchell; Canadian artist Jean-Paul Riopelle; Portuguese painter Maria Helena Vieira da Silva; German painter Hans Hartung; and French painter Pierre Soulages.

Wou-Ki also rekindled his passion for lithography, which was experiencing a creative resurgence at the time. In 1950, he created eight lithographs exhibited by publisher Robert J. Godet. These works caught the attention of poet Henri Michaux, who wrote eight poems to accompany them. This collaboration, marking the start of a lifelong friendship, was published by Godet in the book "Lecture par Henri Michaux de huit lithographies de Zao Wou-Ki" (1950). Michaux introduced Wou-Ki to gallerist Pierre Loeb, with whom he would exhibit until 1957.

Concurrently, Wou-Ki developed a fascination with Shang-dynasty oracle bone script, an ancient form of Chinese writing dating back to around 1500 BC, and began creating works featuring simple figures reminiscent of ancient rock art (petroglyphs). In 1951, Wou-Ki became closely acquainted with architect I.M. Pei, leading to many future collaborations.

In 1952, Wou-Ki embarked on a solo exhibition journey to Switzerland, where he encountered the work of Paul Klee. This encounter sparked a significant shift in his artistic style. Declaring, "No more still lifes or flowers, I am aiming for an imaginary and indecipherable new writing," Wou-Ki embarked on a new artistic direction.

Upon his return to Paris, after brief tours of Italy and Spain, he formed a close friendship with Joan Miró. Arts critic Yann Hendgen notes, "Wou-Ki and Joan Miró first met in 1952 at Galerie Pierre in Paris, and Miró attended the openings of all his exhibitions there. Wou-Ki was deeply touched by this sign of friendship." Despite their 27-year age gap, they frequented the same print workshops, such as Madeleine Lacourière's in Paris and the Polígrafa studio in Barcelona. They also shared many mutual friends, including Eduardo Chillida, Antoni Tàpies, museum director Jean Leymarie, and art historian Kosme de Barañano.

Emotionally affected by the dissolution of his marriage in 1957, Wou-Ki sought solace by visiting his brother Wu-Wai, residing in New Jersey with his wife Phoebe. Together, Wou-Ki and Phoebe, who had studied art history and French, explored New York City, immersing themselves in its museums and galleries.

It was during this time in New York that the artist crossed paths with avant-garde art dealer Samuel Kootz. Wou-Ki collaborated with Kootz until the gallery's closure in 1966. Socially, Wou-Ki became well-connected, forming friendships with Franz Kline, Philip Guston, Adolph Gottlieb, William Baziotes, Saul Steinberg, and Hans Hofmann. He also traveled extensively, visiting the West Coast, Hawaii, Tokyo, and Hong Kong.

While in Hong Kong, he encountered May-Kan Chan, described as "an actress of extraordinary beauty," and they married in 1958. Unfortunately, May-Kan's fragile health required Wou-Ki's dedicated care. For the following decade, amidst personal turmoil that he likened to "living in the middle of a storm," Wou-Ki found solace solely through his art.

In late 1959, Wou-Ki purchased a warehouse in Paris's Montparnasse district, which architect Georges Johannet transformed into a studio for him. It was Samuel Kootz who initially encouraged him to venture into larger-scale paintings, and with his new Parisian studio, Wou-Ki had the space to create these expansive "Hurricane" canvases. However, as noted by Sotheby's, given his challenging personal circumstances, these works posed a significant test to Wou-Ki's energy and resilience, with success achieved only under the most favorable conditions. Among the thirteen years of the Hurricane Period, 1964 stands out as a pinnacle, during which Wou-Ki achieved both physical and spiritual equilibrium, completing just nine canvases, marking the zenith of his artistic prowess.

In 1964 Wou-Ki also produced ten lithographs to accompany André Malraux's "La Tentation de l'Occident" (Temptation of the West). Malraux, the French Minister of Culture at the time, sponsored Wou-Ki's French nationality, which was granted to him in the same year. Additionally, Wou-Ki, who had formed a friendship with the composer in the 1950s, dedicated a canvas to Edgar Varèse in homage the year before he died in 1965.

In 1972, May-Kan succumbed to her illness, plunging Wou-Ki into profound grief. His sorrow deepened further with the passing of his mother soon after. Stricken by loss, Wou-Ki embarked on a journey back to Shanghai, reuniting with his family for the first time in 24 years. During his time in Shanghai, away from his studio, he reacquainted himself with the Chinese brush-and-ink tradition. This tradition was officially prohibited in 1966 with the onset of the Cultural Revolution, during which oil painting supplanted brush-and-ink as the dominant art form. The revolutionary ethos, emphasizing workers, soldiers, and peasants, replaced traditional subjects like landscapes and flora.

In 1970, architect Josep Lluís Sert, renowned for designing Joan Miró's studio in Palma de Mallorca in 1956, reached out to Wou-Ki with news of his acquisition of a hill in Ibiza, where he planned to construct six houses. Entrusting Sert's vision, Wou-Ki agreed to purchase one of the houses sight unseen. In 1972, Wou-Ki relocated to his new home in Ibiza and later erected a studio there according to Sert's original designs. Subsequently, he spent extended periods on the island, both in winter and summer, alongside curator Françoise Marquet, whom he married in 1977.

Around this juncture, New York art dealer Pierre Matisse visited Wou-Ki's studio and offered to showcase his paintings and drawings at his gallery. This gesture proved pivotal for Wou-Ki, as his work had not been exhibited in the city since the closure of Kootz's gallery in 1966.

In 1979, the Chiang Ching Dance Company, led by Chiang Ching, a graduate of the Peking Academy of Dance settled in New York, and collaborated with Wou-Ki, utilizing his paintings as backdrops in the form of slides for their performances. During the same year, Wou-Ki's longtime friend, Pei, extended an invitation for him to create two large-scale ink works for the newly designed Fragrant Hill Hotel in Beijing.

From 1980 to 1984, Wou-Ki assumed a teaching position in mural painting at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs. In 1982, he facilitated a meeting between Pei and Emile Biasini, France's Minister of Culture, which ultimately led to the iconic glass entrance pyramids at the Louvre courtyard designed by Pei.

In 1985, Wou-Ki and Marquet received an invitation to teach at his alma mater, the Hangzhou School of Fine Arts. Additionally, Wou-Ki forged a friendship with Jacques Chirac, the French President, who became one of his most ardent supporters, even writing the preface for the catalog of his first major Chinese retrospective in 1998 in Shanghai. That same year also marked the unveiling of Lisbon's Oriente subway station, featuring a ceramic wall panel created by Wou-Ki.

In 2006, Jacques Chirac honored Zao by appointing him to the Legion of Honour, France's highest recognition. By 2008, Zao had transitioned from painting in oils to watercolor, a medium he continued to explore until 2010. Zao-Wou-Ki passed away in a hospital in Nyon, Switzerland, in 2013. True to his wishes, he was laid to rest at Montparnasse cemetery.

The Art Style of Zao Wou-Ki

Using oil paint, watercolor, and ink, Wou-Ki crafted a distinctive signature style characterized by bold contrasts in color and dynamic linework. Combining gestural abstraction with elements of traditional Chinese landscape painting, his renowned works capture fragments of larger vistas with fluidity, transparency, and ethereal luminosity that mirror the inner essence of the artist himself. Wou-Ki's art delves into profound narratives, encouraging viewers to contemplate their existence within the vastness of the universe.

The so-called "Hurricane Period" of Wou-Ki's career, spanning roughly from 1959 to 1972, derived its name from the grandiose and untamed style he developed, often producing canvases up to six meters in length. This period marked a definitive departure from his earlier, more symbol-laden "Paul Klee" and "Oracle Bone" periods. Rejecting titles for his works, Wou-Ki famously remarked, "I only give the date. I am not a poet. Titles are restrictive." Instead, he pioneered a form of transcendental abstraction that garnered widespread critical acclaim at a time when the validity of painterly abstraction was being questioned.

Wou-Ki resisted being pigeonholed as a "Chinese painter," evident in the early influence of Cézanne and Matisse on his portraits. However, it was his encounter with the work of Paul Klee that truly ignited his artistic journey. Inspired by Klee's abstract symbolism, Wou-Ki began incorporating signs into his paintings, leading to his "Oracle Bone Period." During this phase, he embraced his heritage by integrating ancient Chinese hieroglyphic scripts from oracle bones into his works. Across expansive canvases, Wou-Ki scattered these symbols amidst imaginary landscapes adorned with vibrant color contrasts.

Years:

Born in 1921

Country:

China, Beijing

Gallery: