Joan Miró

Joan Miró, a renowned Spanish artist and one of the pioneers of Surrealism, did not align himself with the surrealists of his era, choosing instead to explore a diverse array of artistic styles, including Expressionism and lyrical abstraction.

Biography of Joan Miró

Joan Miró i Ferrà was born in Barcelona, Catalonia. His father, Miquel Miró i Adzerias, worked as a silversmith and watchmaker, while his mother, Dolors Ferrà i Oromí, was the daughter of a cabinet maker from Palma de Mallorca. They raised him in Barri Gòtic, the heart of old Barcelona.

At 7, Miró started taking drawing classes at a private school. When he turned 14, he joined a business school in Barcelona, although he also attended La Llotja - Escuela Superior de Artes Industriales y Bellas Artes, against his father's wishes. At La Llotja, he received instruction from Modest Urgell and Josep Pascó.

After completing three years of art studies, Miró reluctantly took a job as a clerk in a drugstore, as his parents had desired. However, the demanding work took a toll on his health, leading to a severe illness that brought him close to a nervous breakdown, followed by a bout of typhoid fever. Concerned about his well-being, Miró's parents allowed him to return to his art studies. From 1912 to 1915, he attended Francesc Galí’s Escola d’Art in Barcelona, a free-spirited school known for its influence on contemporary foreign painters and its focus on literature and music. During this time, Miró developed the ability to draw through the sense of touch rather than relying solely on sight.

In 1913, the artist joined the "Cercle Artistic de Sant Lluc" to participate in drawing classes and to have the opportunity to showcase his work alongside fellow members. The Cercle Artístic de Sant Lluc was founded in 1893 by Joan Llimona, Josep Llimona, Antoni Utrillo, and Alexandre de Riquer as a response to the anticlerical tendencies in modernism. This society was known for its strong advocacy of Catholic morals and family values. These principles were reflected in their prohibition of artistic nudes, and all members aspired to embody the humble qualities reminiscent of medieval guilds. Eventually, Miró and a small group of artists within the Saint Lluc society formed their own subgroup, naming themselves the Courbet group in admiration of the painter Gustave Courbet for his radical approach to art.

Around 1915, the Dada movement was on the rise, and Miró began immersing himself in the works of avant-garde Surrealist poets like Apollinaire and Pierre Reverdy. His time in Barcelona was significantly influenced as he frequented the Galeries Dalmau, a focal point for avant-garde art that featured pieces by numerous foreign artists. José Dalmau, the gallery owner and art dealer, provided encouragement and assistance to Miró, helping him organize his inaugural solo exhibition at his Barcelona gallery. However, the artist's first exhibition faced harsh ridicule.

In 1919, Joan Miró embarked on his maiden journey to Paris, where he visited Picasso in his studio. This marked the beginning of a dual residency for Miró, as he divided his time between Paris and his parent's summer home and farm in Mont-Roig del Camp, Spain. During this period, he created "The Farm," a painting that signaled a shift toward a more distinct and individual style infused with certain nationalistic qualities.

Also in Paris, Miró forged friendships with Max Jacob, Pierre Reverdy, and Tristan Tzara, becoming a part of the Dada circle and actively participating in their creative activities. He delved into the writings of Nietzsche, the German Romantic poets, and the Pre-Socratic philosophers, as well as the poets championed by the Surrealist group, including Jarry, Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Lautréamont, and Rimbaud. In 1921, José Dalmau once again organized Miró's first solo exhibition, this time in Paris at the Galerie la Licorne.

By 1925, Joan Miró had unequivocally departed from figurative art as he ventured into the realm of Surrealism. His breakthrough came with an exhibition at the Galerie Pierre, a significant Surrealist event. André Breton, a leading figure in Surrealism, remarked that Miró's work exuded a remarkable innocence and freedom. Following this, he became part of the inaugural Surrealist exhibition at the Galerie Pierre in the same year.

During the Spanish Civil War, Miró lived in France, deeply distressed and profoundly affected by the tragic events unfolding in Spain. During this period, he briefly returned to a form of realism influenced by this turmoil. In 1937, while in Paris, he painted a mural for the Spanish Republic's pavilion at the World's Fair, titled "The Reaper (Catalan peasant in revolt)," which unfortunately later disappeared. Four years later, he returned to Spain, this time to Varengeville-sur-Mer on the Normandy coast, where he stayed until the area came under attack by Nazi bombings. Although Miró was not actively involved in politics, his artwork during this challenging period began to reflect a certain brutality, characterized by distortions and garish colors.

Additionally, in 1941, while Europe was still engulfed in war, the Museum of Modern Art in New York hosted the first retrospective exhibition of Miró's work, signaling the enduring international impact and recognition of the artist.

Starting in 1944, the artist experimented with ceramics, bronze sculpture, and printmaking. His deep connection to his Catalan heritage, particularly with decorated Catalan pottery, significantly influenced his work. He collaborated with Josep Llorens i Artigas on several pottery projects in the years to come, with Artigas being his lifelong friend and artistic partner. Notably, Miró's creations "Wall of the Moon" and "Wall of the Sun" for the UNESCO building in Paris received the prestigious Guggenheim International Award.

In recognition of his contributions to graphic art, Miró was awarded the Grand Prize for Graphic Work at the Venice Biennale in 1954. The following year, in 1955, his artwork was featured in the inaugural Documenta exhibition held in Kassel.

In the 1950s, Joan Miró's involvement in monumental and public commissions gained momentum. He drew inspiration from young American painters, prompting him to create large-format paintings within the studio designed for him by Josep Lluís Sert in Palma, Majorca, where he had resided since 1956.

As the Franco regime in Spain drew to a close, Miró's inner political activist stirred to life. He used all available means of expression to voice his criticism of the overall cultural and political situation in his beloved homeland, with a particular focus on Catalonia.

Remarkably, Miró's artistic output extended to creating over 250 illustrated books, collectively known as "Livres d'Artiste." These were essentially works of art presented in the form of books, typically published in small editions.

In honor of Miró's profound impact on the art world, the Fundació Joan Miró, a museum dedicated to his work, was established in his hometown of Barcelona in 1975, and another, the Fundació Pilar i Joan Miró, was established in Palma de Mallorca, in 1981. The establishment of the Joan Miró Foundation was made possible by the artist's wife, Pilar Juncosa, who shared her husband's passion for his art and played a pivotal role in setting up the foundation. She generously donated or loaned a substantial portion of her collection of Miró's works to the foundation.

Joan Miró, after a century-long life that witnessed two world wars and countless artistic achievements, passed away in 1983, leaving behind a legacy marked not only by monumental accomplishments but also by an extensive and timeless body of work.

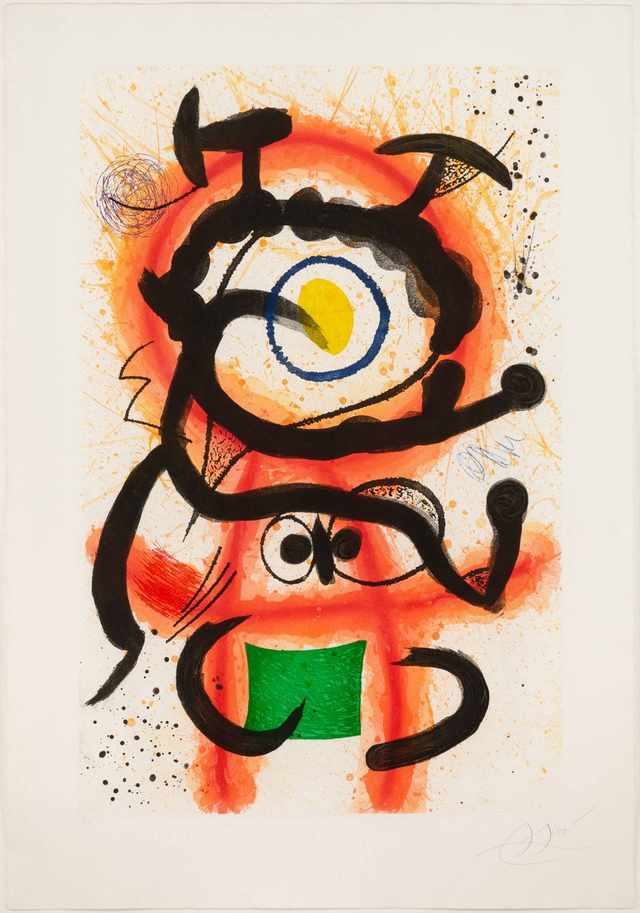

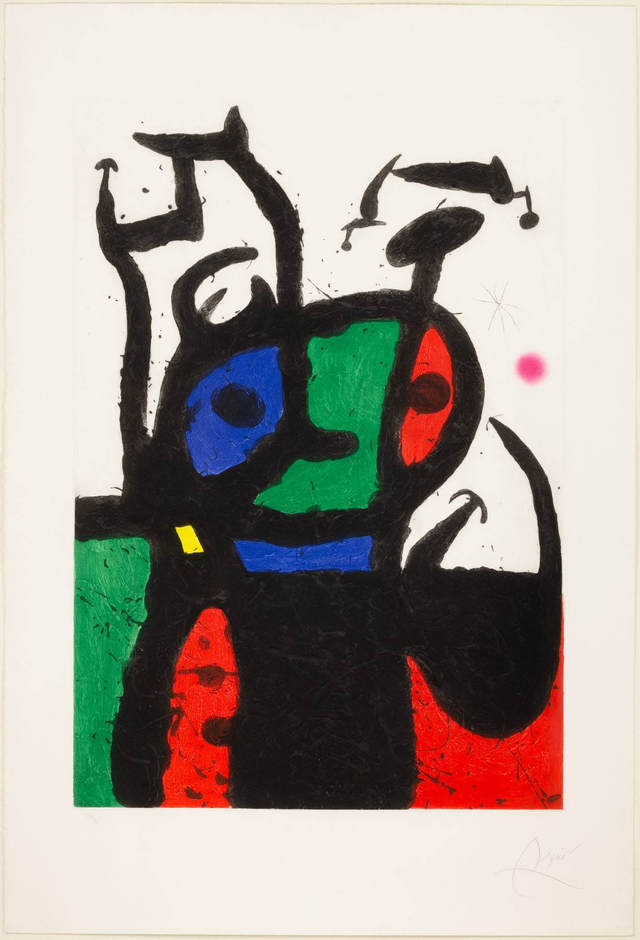

Joan Miró's Art Style

A significant wellspring of inspiration for Joan Miró was the rich folklore of his cherished Catalonia, an influence that would permeate his art from its inception to its end. Throughout his life, Miró maintained an enduring fascination with the interiors of frescoed churches dating from the ninth to the twelfth century. These frescoes featured a relatively crude execution, employing simple, flat, and cartoon-like imagery. Miró's art bore the imprint of these church frescoes in several ways. He frequently used primary colors with bold black outlines, set against a darkly shaded surrounding background, and treated space as a flat surface, echoing the aesthetics of these frescoes. Much like children, Miró played with scale, enlarging certain elements far beyond their natural proportions in his artworks.

In 1923, a significant transformation occurred in Miró's art, marked by a shift towards more sign-like forms. His work began to incorporate flat shapes and lines, often rendered in bold black or vibrant colors, suggesting subjects in a sometimes cryptic manner. A notable example of this representational style from this phase is "Catalan Landscape (The Hunter)" from 1923, where he used a triangle to symbolize the head, curved lines for the mustache, and angular lines for the body. This adoption of pictorial sign language became a central theme in Miró's artistic journey, persisting throughout the remainder of his career.

In 1928, Miró traveled to the Netherlands and embarked on a series of paintings inspired by Dutch masters. During this period, he openly declared his intention to "assassinate painting" as a rejection of bourgeois art and explored less conventional means of artistic expression, such as collage and assemblage. In the same year, he created his first "papiers collés" (pasted papers).

Upon returning to Barcelona in 1932, Miró continued to paint in a new manner, creating art that was visually more direct and assertive. He engaged in experiments with a range of materials, including wood, metal, hardboard, various objects, and paper. In the early 1930s, Miró shifted his focus toward creating Surrealist sculptures, employing painted stones and found objects.

Throughout World War II, the artist drew inspiration from the night, music, and stars, embarking on the creation of a series titled "Constellations." These paintings featured black dots representing stars against a white backdrop, using gouache and thinned oil on paper.

Miró shifted his focus towards printmaking, dedicating a significant portion of his creative energy to this medium from 1954 to 1958. His work in printmaking encompassed various processes, including engraving, lithography, etching, and the use of stencils known as "pochoir."

Miró also pioneered the development of automatic drawing, a technique reinvented by the Surrealists as a means of expressing the subconscious. He harnessed automatic drawing as a way to break away from established painting techniques, with many of his paintings commencing as spontaneous, automatic drawings.

Years:

Born in 1893

Country:

Spain, Barcelona

Gallery:

Galleria d'Arte Maggiore g.am.

Landau Fine Art

Helly Nahmad Gallery

Christopher-Clark Fine Art