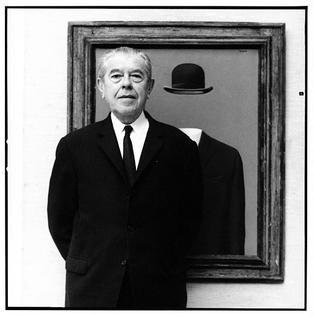

René Magritte

René Magritte possessed a remarkable ability to infuse seemingly mundane subjects with a profound sense of magic through his Surrealist imagery. The Belgian surrealist artist had a knack for painting everyday objects deliberately removed from their typical contexts, incorporating them into compositions that compelled viewers to reconsider things they often took for granted.

Biography of René Magritte

René François Ghislain Magritte was born in Lessines in 1898. He was the eldest son of Leopold Magritte, a tailor and textile merchant, and Regina, a retired milliner who gave up her vocation after marriage. Financial difficulties often loomed over the family, leading to frequent moves in search of lower taxes and reduced living costs. Magritte's childhood was constant travel and relocation. His artistic journey began in 1910 when he started drawing.

On March 12, 1912, tragedy struck as Magritte's mother, Regina, took her own life by drowning in the River Sambre. This was not her first suicide attempt, as she had a history of such tendencies. This tragic event was just one of the many influences from Magritte's childhood that played a significant role in shaping his future career.

According to the eerie legend that suggests 13-year-old Magritte witnessed the retrieval of his mother's body from the water, supposedly, his mother's dress covered her face when she was found, an image that later inspired several of Magritte's oil paintings from 1927-1928 featuring people with their faces obscured by cloth. However, recent research discredits this story, suggesting it may have originated with the family nurse.

Magritte's earliest oil paintings, around 1915, exhibited an Impressionistic style, reflecting his early inclination toward long-forsaken and established artistic styles. From 1916 to 1918, after World War I, Magritte pursued studies at the Academie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels under the guidance of Constant Montald. However, he did not find Montald's guidance particularly inspiring, leading him to gradually distance himself from Impressionism and its principles. Between 1918 and 1924, Magritte explored the possibilities and concepts of Futurism and Cubism, with many of his works during this time featuring female nudes.

In 1922, Magritte married Georgette Berger, whom he had met in 1913, a year after his mother's passing. In the following years, the artist served in the Belgian infantry in the Flemish town of Beverlo. Additionally, he worked as a draughtsman in a wallpaper factory and pursued a career in poster and advertisement design until 1926.

In a twist of fate, Magritte secured an opportunity in 1926 to sign a contract with Galerie la Centaure in Brussels, enabling him to devote himself to painting full-time. In the same year, he created his first surreal oil painting, the now-legendary "Lost Jockey" (Le jockey perdu). Despite being recognized today as a classic of modern art, "The Lost Jockey" faced criticism when Magritte held his first exhibition in 1927, with critics harshly disparaging the young painter's work.

Disappointed by the failure and feeling insulted by Belgian critics, Magritte relocated to Paris. There, he formed a friendship with André Breton and became involved with the Surrealist group, which warmly embraced his ideas. However, despite an initially successful stint in France, Magritte soon grew bored. His international contract with Galerie la Centaure came to an end in 1929, leaving him financially strained. Consequently, the artist decided to return to Brussels the following year.

Back in Belgium, Magritte resumed his work in advertising. He and his brother Paul established an agency that provided him with a steady income. Nevertheless, the artist continued to paint privately, further developing his style. Some of his paintings began to gain attention without active promotion, catching the eye of the Surrealist patron Edward James. Generously, James allowed Magritte to live rent-free in his London home, where the artist continued to create. During his time in London, Magritte refined his style but again was not able to make the impact he desired.

Throughout his stay in London, Magritte maintained correspondence with André Breton. Their artistic relationship revolved around sharing ideas and concepts, solidifying their friendship that developed during Magritte's time in the City of Light, Paris.

Soon, the artist returned to Brussels due to financial challenges and a lack of success. He re-entered the family business, continuing his routine of working in advertising during the day and painting at night. During the German occupation of Belgium in World War II, Magritte chose to remain in Brussels, a decision that caused a rift with André Breton, who had hoped for Magritte to be by his side in Paris.

In the war years of 1943-44, Magritte briefly adopted a colorful, painterly style known as his "Renoir Period." This artistic interlude is widely interpreted as a reaction to his sense of alienation and abandonment while living in German-occupied Belgium. Just as with the loss of his mother, the tragedies of World War II seemed to have a profound impact on Magritte's art, leading him into darker creative territory than he had explored before.

In 1946, as the horrors of World War II began to recede into the past, Magritte renounced the violence and pessimism that had characterized his earlier work. He joined several other Belgian artists in signing the manifesto "Surrealism in Full Sunlight." During this period, the artist supported himself by producing counterfeit paintings supposedly created by artists such as Picasso, Van Gogh, Manet, and Paul Cezanne—an illicit endeavor he later expanded to include the printing of forged banknotes during the challenging postwar period. By the end of 1948, he had returned to the style and themes of his prewar surrealistic art.

Magritte's work gained significant popularity in the 1960s, and his fame reached its zenith after his death, a pattern often observed with many great artists. His iconic imagery has exerted a profound influence on pop, minimalist, and conceptual art. His distinctive style has also become one of the most instantly recognizable trademarks of the Surrealist movement. Magritte's highly figurative style often draws comparisons to the work of artists like Salvador Dalí and Giorgio de Chirico. His persistent exploration of objects has not only influenced but has also paved the way for numerous emerging artists. For decades, Magritte's art has captivated and entertained the art world, remaining a perennial source of fascination within art circles.

René Magritte's Art Style

As he continuously evolved in terms of style and concepts, René Magritte aimed to develop an approach that steered clear of the stylistic complexities in most modern paintings. While some French Surrealists were experimenting with innovative techniques, Magritte settled on an illustrative technique that distinctly conveyed the content of his paintings. It's worth noting that the men wearing bowler hats, a recurring motif in the artist's works, can be interpreted as self-portraits. Magritte was deeply intrigued by the interplay between textual and visual signs, and some of his most renowned works integrated both words and images. While these pieces often exude an aura of mystery characteristic of Surrealism, they also seem to be driven by a spirit of rational exploration and wonder concerning the potential misunderstandings inherent in language.

Repetition played a significant role in Magritte's artistic strategy, not only within individual paintings but also in his production of multiple copies of some of his most significant works. This interest in repetition may have been influenced in part by Freudian psychoanalysis, where repetition is considered a sign of trauma. Freud's ideas were a significant influence on Breton's original ideas associated with Surrealism, and Magritte was well-versed in the concepts of the father of psychotherapy. Additionally, his background in commercial art may have contributed to his questioning of the conventional modernist belief in the unique, original work of art.

In his iconic work, "The Treachery of Images," Magritte depicted a hyper-realistic pipe and accompanied it with the text "This is not a pipe." This deliberate contradiction was a central theme in Magritte's art, urging us not to trust our eyes blindly. He reminded us that an art object, regardless of its realism or convincing appearance, is not real—an essential lesson in the tendency to deceive ourselves into believing that what we see is an unaltered reality.

Years:

Born in 1898

Country:

Belgium, Lessines

Gallery:

Galleria d'Arte Maggiore g.am.

Van de Weghe

Landau Fine Art

Vedovi Gallery