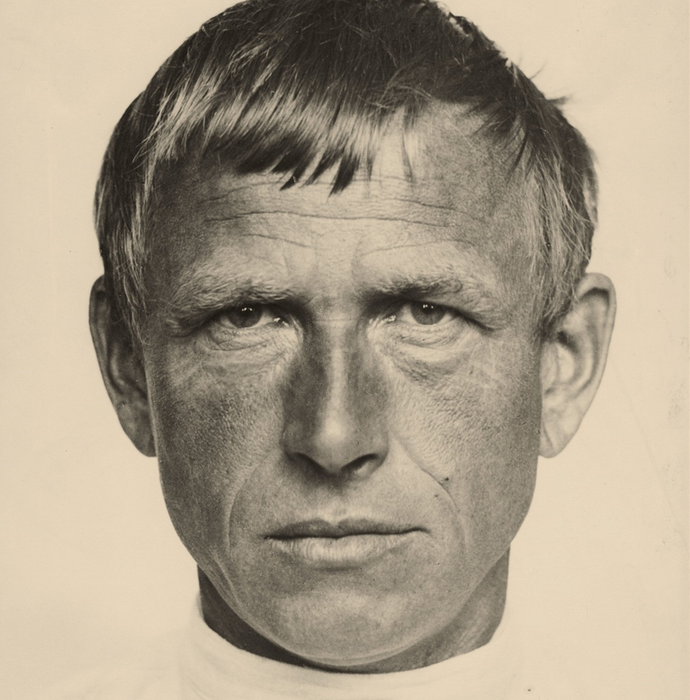

Otto Dix

Otto Dix was one of the most influential German painters in defining the popular image of the Weimar Republic in the 1920s. His work is central to the Neue Sachlichkeit ("New Objectivity") movement, which also included artists like George Grosz and Max Beckmann in the mid-1920s.

A war veteran deeply affected by his experiences in WWI, Dix initially focused on portraying wounded soldiers. However, at the height of his career, he also created provocative nudes, depictions of prostitutes, and sharply satirical portraits of prominent intellectuals in Germany.

Biography of Otto Dix

Wilhelm Heinrich Otto Dix was born on December 2, 1891. His father, Franz Dix, was a mold maker in an iron foundry, and passed on his strength of character and steel-blue eyes to Dix, while his mother, Pauline, a seamstress, instilled in him a love for music and poetry.

Dix first exhibited his artistic talent, particularly in drawing, during elementary school. At the age of ten, he modeled for the painter Fritz Amann, and his positive experience in the studio inspired him to pursue a career in painting. His school art teacher, Ernst Schunke, supported his artistic ambitions and helped him secure financial aid. As part of the award requirements, Dix had to learn a trade while continuing his art studies with Schunke, so he spent four years apprenticing as a decorator.'

In 1909, Otto Dix began his studies at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts. Dresden was a vibrant cultural hub with a thriving art and music scene, renowned for its large exhibitions and events. Dix did not face financial difficulties during his time at the Academy and after his first semester, he was exempted from paying fees and received a stipend. He supplemented his income by selling small portraits, genre paintings, and coloring photographs.

Although the Academy offered more of a craft-oriented education rather than formal academic training in painting, Dix was essentially self-taught. He did, however, experiment with sculpting under Richard Guhr's guidance. The artist created a bust of Friedrich Nietzsche that was purchased by the Dresden State Museum but was later destroyed by the Nazis.

Through extensive study of the Old Dutch, Italian, and German Masters, Dix taught himself to paint using their techniques, focusing on building up layers of paint to achieve depth and luminosity. He was also influenced by Expressionists and Post-Impressionists, particularly after seeing a Vincent van Gogh exhibition in 1913. During this period, Dix primarily painted portraits and landscapes, experimented with pen and ink, and produced his first prints.

When World War I began, Otto Dix eagerly volunteered for service and was drafted into a field artillery regiment. By 1915, he was a machine gunner on the front lines in France, where his enthusiasm was quickly dampened by the horrors of battle. Despite being wounded several times, Dix managed to create sketches of the tragic scenes he witnessed. After the war, he resumed his art education at the Dresden Academy of Art, studying under Max Feldbauer and Otto Gussman from 1919 to 1922.

Post-war Dresden was a shadow of its former self, no longer a seat of government and plagued by a significant drop in income and severe rationing. Despite this, the artistic scene adapted and revived with great vigor. In the context of fluctuating values and political ideas, Dix was driven to experiment further. He had already incorporated Futurism and Cubism during the war years; now, he began integrating Dadaist and Expressionist elements into his work.

In 1919, Otto Dix co-founded the Dresdner Sezession Gruppe and participated in two of their exhibitions at the Galerie Emil Richter. During this period, the artist created surreal portraits, and woodcuts, and explored collage and mixed media.

After 1920, Otto Dix synthesized and transformed various artistic styles into his unique brand of realism. Over the next few years, the artist created some of his most disturbing canvases depicting sexual violence, murder, and cruelty. An example of this grotesque yet poignant imagery is "Skat Players (Card-Playing War Cripples)" (1920). In 1921, Dix exhibited his work in Berlin and Dresden before moving to Düsseldorf in 1922. This relocation marked an important shift as he studied with new teachers, Heinrich Nauen and Wilhelm Herberholz, and became part of both Johanna Ey's art salon circle and the German modernist group Das Junge Rheinland.

In 1923, Dix married Martha Koch, and over the next decade, the couple had three children, all of whom the artist captured on canvas throughout their childhoods.

Throughout the 1920s, Dix participated in many significant exhibitions of new art in Germany. Most notably, he was included in the "Neue Sachlichkeit" exhibition at the Kunsthalle Mannheim in 1925, which gave its name to the movement Dix would be forever associated with. Neue Sachlichkeit evolved out of Expressionism but incorporated qualities of the classical, linear realism that was becoming prevalent in Italy and France.

The Neue Sachlichkeit style, though more sober and realistic than previous artistic movements, remained highly critical in the hands of artists such as Otto Dix and George Grosz. Some of these artists, known as Verists, adopted an aggressive and cynical approach, while others, less abrasive, were described as Magic Realists. As a Verist, Dix used his portrait skills to critique the decadence and debauchery of Weimar society in works like "Metropolis" (1927-28). Other notable pieces from this period include his triptych "The War" (1929-32).

In 1931, Dix was appointed to the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin. That same year, his work was exhibited across Germany and at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. However, his renown was short-lived as the Nazis began targeting him, labeling his art as immoral. Consequently, Dix was forbidden from exhibiting in Germany. Despite this, he traveled to Switzerland several times during the mid-1930s and participated in several exhibitions there.

Forced to join the Nazi government's Reich Chamber of Fine Arts in 1934, Otto Dix still managed to express himself through his art. His work "Seven Deadly Sins" (1933) parodied Adolf Hitler as the embodiment of Envy. Sent to a rural outpost, Dix depicted the surrounding landscapes in his artwork. In 1939, he was arrested on charges of plotting to kill Hitler, but the charges were eventually dropped. At the end of the war, he was captured by the French and held prisoner until 1946. During his imprisonment, he painted a triptych for the prison camp chapel.

After returning to Germany, Dix resumed his career, continuing to exhibit his works and creating lithographs. He documented his war experiences and their effects in his art, picking up where the war had interrupted his prolific output.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Otto Dix traveled extensively and exhibited his work frequently. He was appointed to membership in numerous art academies in Florence, Berlin, and Dresden. Dix continued creating prints and participated in a short documentary film in 1965. In 1967, after traveling to Greece, he suffered a stroke that paralyzed his left hand. The artist died in 1969.

The Art Style of Otto Dix

Otto Dix is one of modern painting's most incisive satirists. While many artists in the 1910s had turned to abstraction, Dix revisited portraiture and infused it with sharp caricatures of prominent figures in German society. His narrative works are renowned for their critique of the corruption and immorality prevalent in modern urban life.

Initially drawn to Expressionism and Dada, Dix, like many of his contemporaries in Germany during the 1920s, was influenced by Italian and French trends, leading him to adopt a cold, linear drawing style and more realistic imagery. Over time, his approach evolved into something more fantastic and symbolic, as he began to depict nudes as witches or symbols of melancholy.

Dix consistently balanced his realism with a tendency toward the fantastic and allegorical. For instance, his portrayals of prostitutes and injured war veterans serve as symbols of a society scarred both physically and morally.

Despite his keen eye for depicting the human figure, Dix’s early focus on crippled veterans and use of caricature reveals his discomfort with celebrating the human body and spirit in his art. n the early 1930s, his work took on a darker, more allegorical tone, leading to his being targeted by the Nazis. Consequently, he shifted away from social themes to explore landscapes and Christian subjects.

Years:

Born in 1891

Country:

Germany, Untermhaus (now a part of the city of Gera, Thuringia)

Gallery: